COSMOS is almost coming to an end. The project, not the universe. In a few weeks the full evaluation report that describes the impact COSMOS has had on students, teachers and schools will be available. This blog provides an insight and a reflection on some key results from the impact the project has had on students.

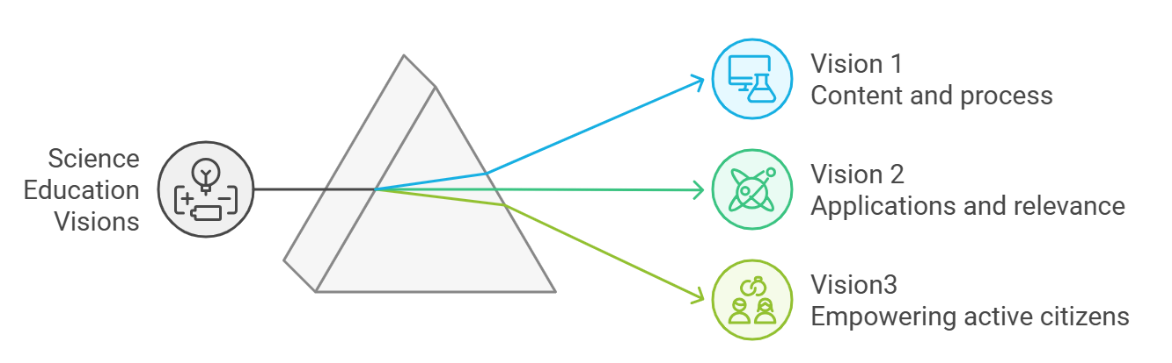

But let’s start with asking why. Why do we, at COSMOS, actually want schools to work on ‘open schooling’ through their science education? After all, can't you just teach science in the classroom, with the textbook at hand? What extra does it offer bringing in open schooling? Questions like this are about visions of science education. Researchers talk about three possible visions in this area:

Teachers often navigate between these three visions, and it can be discussed if each one of these actually fits within the role that societies have given to education. Very clearly, Vision 1 belongs in the science classroom, many subjects need a firm basis of facts to build on. But build towards what? Vision 2 can help experience the relevance of what you learn as a student. It can help answer the question ‘why do we need to know this?’. Vision 3 takes pupils even further into their role as citizens in society and wants them to experience that they themselves can contribute to that society. In the future, as adults but also now already, as kids. Not all science education topics fit equally well with each of these three visions. Teaching science using socio-scientific issues in particular are appropriate for meeting the needs of all three visions. In the COSMOS project, we chose SSIBL (socio-scientific inquiry-based learning) as the didactic approach to do this. A lot of the blog posts here on our website show how teachers did this in their teaching.

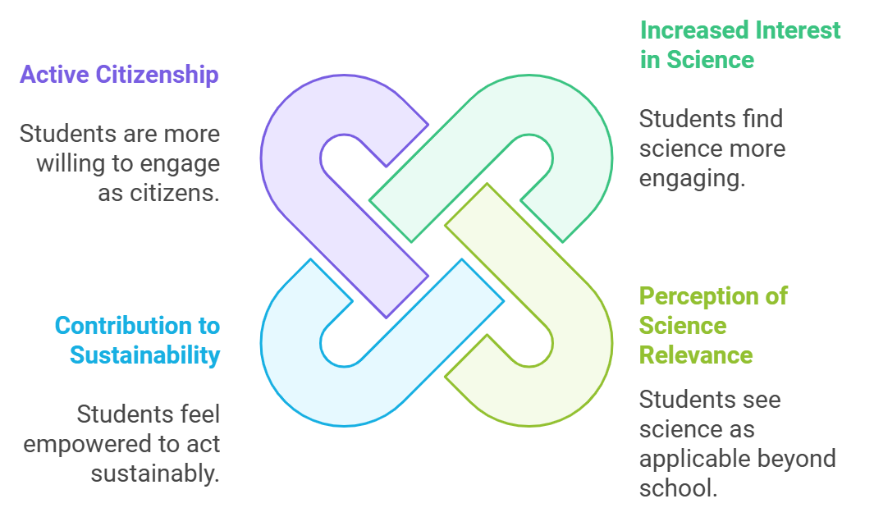

COSMOS did not simply assume that by applying SSIBL in the classroom, open schooling would also become a success. We developed an evaluation approach that included questionnaires and group discussions to gain insight into what students in participating schools were learning. More than 1000 pupils from about 20 schools spread across the COSMOS countries, participated in the evaluation study. In doing so, we note some very encouraging results. We see an increase in interest in science:pupils indicate after the SSIBL implementation in their schools that they experience science as interesting more than before. In line with Vision 2 of science education, we also see in the results that they grow in their perception of science as relevant. In other words, they experience that what they learn in their science education is not just for school, but that it is also useful beyond the school walls and finds application in society and their everyday lives.

Since, in line with the open schooling philosophy, we were also interested in Vision3, we included that too in the evaluation. And here, too, the results are encouraging. We see that because of learning science through SSIBL, pupils indicate that they are more knowledgeable about how they themselves can contribute to a more democratic and sustainable society, that their belief in their own abilities to act has been strengthened, and that they are more willing to take on their role as active citizens.

Although the results do not indicate a very large change, the moderate shifts we observe in the evaluation are statistically significant. They show that teachers, together with partners from outside the school, can apply SSIBL to build on Vision1 in their teaching to take impactful steps towards Vision2 and Vision3. At COSMOS, we find this very positive and encouraging because it shows that our approach strengthens pupils' attitudes towards science as well as their active citizenship: learning science for school and for life, for now and for the future!